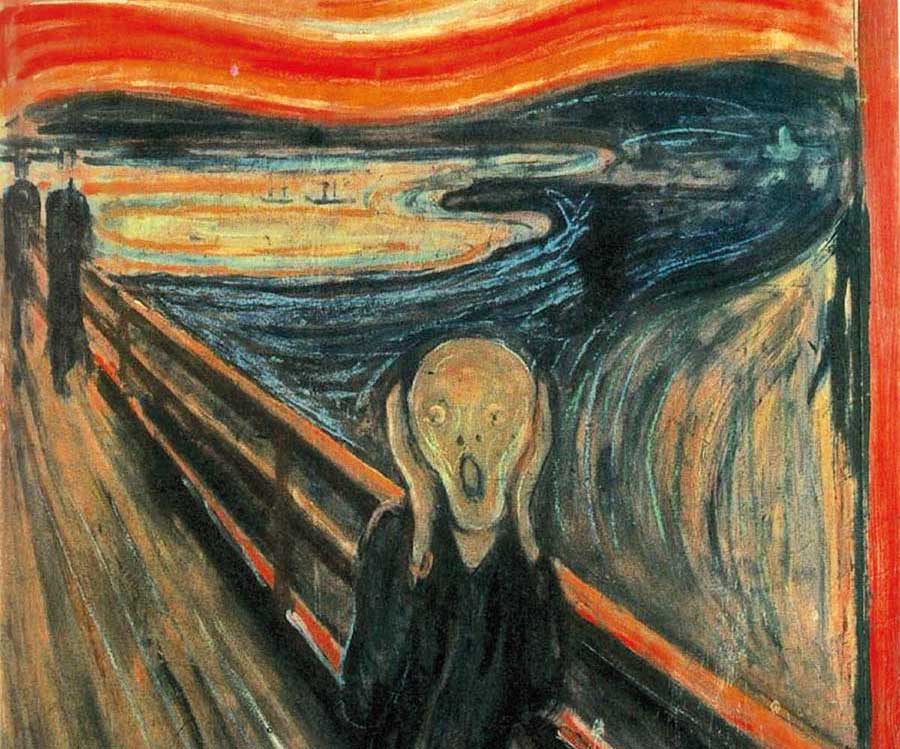

“Maybe for a moment, listening or reading, our conscience is revived from the stupor to which the world has relegated it: but too often everything returns to the status-quo. Instead, we want to give voice to the scream that wells up within us in the face of so much human wickedness.”

Mother Elvira (Founder of over 100 communities worldwide, committed to the rehabilitation of people with addiction to drugs.)

Several friends have asked me to describe an average day in Uganda. This I have found difficult. It is not just the basic living conditions, the dusty roads and the hostile heat, as these could all be the context of an exciting adventure in the Australian outback! The defining feature is a heavy grief that invades your being; a silent, tearless sorrow that, if allowed expression, could overwhelm you. This has enabled me to understand why people here are so stoic: their emotions are paralysed by incomprehension of what they have been through. In order to process the impact of this grief, I have found myself retreating into silence to seek a way forward.

Many years ago, I walked through a long disused railway tunnel and reached a point where it became pitch black. I did not know whether to turn back or keep going. Deciding on the latter, I used the wall of the tunnel to get my bearings and slowly inched my way forward. Eventually I saw a pinprick of light in the distance that marked the exit of the tunnel. This is what the journey of Third Hope is like. It might be expected that we are ‘full of vision and enthusiasm for the work’, but here we have to disappoint. We are inching our way forward whilst hoping and trusting there is light at the end of the tunnel.

Alongside this residual grief of war there is the general chaos caused by a lack of infra-structure. On any ordinary day the delays and disruptions of living without effective police, government services, transport, power, running water and sanitation are unrelenting. Then there are the regular waves of disruption caused by being in a volatile political area confounded by the vicissitudes of poverty. We were in Uganda through the unsettling period of the elections, where sporadic violence in the North threw Gulu into a state of emergency. There was a malaria epidemic that took many lives, young and old, and we were regularly attending funerals to mourn with families that had lost loved ones. There has also been increasing violence over land wrangles. The resettlement of thousands of people after many years in displacement camps has caused heated disputes over boundaries. Some are calling these conflicts ‘The Second War’ and, needless to say, it is the widows and orphans who suffer most. All of the above are the background to an average day in Uganda and need to be acknowledged before one can begin the, ‘We’re up before dawn in order to light the charcoal stove’ narrative!

Living here makes it clear that war leaves a destructive, debilitating trail and recovery is complex for those who have endured its brutality. This is the case the world over, a fact brought home to me when back in the UK and watching Songs of Praise. The programme featured a 92 year old Conscientious Objector from the Second World War who served in the ambulance service and had participated in the clearing of Auschwitz. Throughout his testimony, he spoke with stoic reserve until he began to talk of two young Romanian children he had discovered at the point of death in the medical experimentation ward. Tears came to his eyes and his voice wavered; he could remember their names and as he related their suffering, it was clearly as real to him as it had been that day sixty years earlier. His pain communicated the way the wounds of war never leave one’s heart but linger like a shroud over the optimistic rhetoric of recovery.

This does not mean, however, there is no hope of recovery from war. Instead it shows that the recovery must address head-on the deep pain residing in people’s hearts. And in order to respond to the problem, it is necessary to feel the pain. On a normal day, therefore, we work with this backdrop of pain that threatens to break forth in a piercing scream like that of Munch’s iconic painting. Often the ‘doing’ is frustrated by the sheer effort of ‘being’; and to ‘be’ is all we can ‘do’. Yet I see that this ‘being’ is rewarded with friendship and openness that begins to shed light on a way forward. We can only hope that as we persevere, the scream will slowly transform into a cry of freedom for the oppressed.